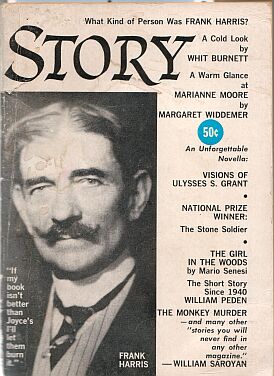

The following account was printed in Story magazine in September 1964. In it the editor of the magazine, Whit Burnett, recalls a meeting with Frank Harris in Nice, in 1926.

He had begun with politics, the intensity of his damnation of the egotistic Mussolini having brought him close to my knee, which to emphasize a point, he struck now and then with his strong, practical-looking hand. Once or twice from his seat on a chaise longue he pulled at my chair, twisting me around to burn me with the force of his declarations.

And then, through the French debts and after his damnation the prejudiced critics of Straight-Forward Literature in the English speaking world, my host, rising, stood for a moment, dramatically, surveying the scope of his subjects. The afternoon sun of Nice, slanting through the windows, fell upon his straight, strong figure, his dark blue suit with its fine white stripe, his white sport shoes with their ornate yellow leather trimmings, his neat, precise puissant totality.

Before that afternoon I had never seen the man.

“You devil!” he had greeted me. “Sit down. You choose the very worst possible time to call on me. This is when I sleep. Didn’t you know that?”

I had begun to leave, offering my apologies for having accepted his written invitation to come to see him “at once.” I was over-ruled. I sank back, and as my host strode about, halting suddenly now and then to bore me through with vigorous assertiveness, I felt the paucity of my youth - 26 in the presence of his 70-odd - becoming grossly apparent among the long-housed bric-a-brac of his many talented friends.

My host continued.

“I said to Caillaux,” he said. grasping my knee. “it’s as plain as the nose on your face! I told Caillaux how to solve his French debts… No wonder Italy lets a Mussolini come in and rule her, Wouldn’t any country these times - when everybody stands around helpless - if a man, I don’t care what kind of one, rose up and said, ‘I’ll make your money good, I’ll make good times, I’ll do this, I’ll do that?’ But - Cuillaux wouldn’t listen to me. “

I lost the face of my host among the faces of Messrs. Chesterton, Bennett. and Wells, faces drawn in caricature and fronting on me from their separate frames on a patchwork wall of pictures. And then, beyond a copy of an English periodical (the cover pencil-marked at a review of my host’s latest work) my eyes fell on the pooping eyes of Oscar Wilde languidly looking out of a faded sepia print-the tired eyes of sophistication.

My host ended another verbal paragraph, and then, noticing my glance, he strode to the wall of trophies.

“You should see some of these things,” he said.

He rested his hand on a small clay figurine, a woman in loose Greek robes.

“Genuine Tanagra,” he said. “Got it in Algeria more than fifty years ago.”

“Fifty years ago!”

“Yes - 1876!”

He beamed good-naturedly and turned on his heel. Emphatically a well-preserved figure of a man, he narrowed his eyes in concentration as his thoughts focused on his life - his large mouth firm, a full-blown moustache still audaciously black and whisked into rigidity, and his hair although graying glossily, yet rich in texture, luxuriantly waved across his head.

“I’m 70-odd,” he added. He was blossoming.”Seventy-odd, not just seventy!”

I was impressed.

“Of course you know the secret?” The eyes of Oscar Wilde stared at us, a dreamy, quiet disdain.

“No.”

His attention, for the moment. was diverted. The black-haired maid, smart in her neat white uniform, slipped in with the Paris Herald and the continental edition of the Chicago Tribune. Her master accorded her a smile. She tiptoed from his presence.

“Parentage,” he said. “You know,” he continued, “once I tried to write bits for a paper in London and one day the editor said to me, ‘Frank, why don’t you write us something funny? There’s great demand for it.’ ‘All right,’ I said. ‘but I must have ten guineas for it, not the usual five.’ ‘Very well,’ he said. ‘And I must be paid now in advance. if you want it.’ ‘All right,’ he said. So I went home and later brought him back a piece. It started:

“ ‘Most everyone is willing, even anxious, to give you advice on the wife you choose. But wives, it seems to me, are not so very important. Any kind of a wife will do. What seems to me to be important is advice on what kind of parents a man chooses.

“ ‘Now I should say this is a great responsibility and one must choose as follows: First they must be young and in love with each other. And then the father should be a sailor. For a sailor is seldom at home, often away on the sea for three years on end. And when he does return, he is capable of making A MAN!’

“I must say,” my host concluded, “although I got paid well enough, the article never appeared.”

He returned to the little object still in his hand.

“She lost her head in Nice here,” he fingered the charming Tanagra, “and they chipped the base in New York.”

“Is that a Cimabue there?” I asked.

“It is. And there’s a Matisse.”

A pencil sketch, jeune fille, recumbent, stomach upward, nude, signed. We passed on.

“But here’s the real thing,” he said, stopping before a newly framed picture. “Matisse stood half an hour in front of that. ‘Frank, he said to me, ‘that’s lovely. What is it, actually. an etching or a dry-point? Ha, ha!”

“It is a question.” We edged toward the drawing of the lady, recumbent, stomach upward, eyes rounded, navel rounded, kneecaps rounded, all in a rain of fine sepia lines.

“The answer is,” he said leaning over closer. it’s both. Both! Ha, ha! Etched in straight lines as it should be, and then carefully gone over in dry-point. Marvelous thing! A Zorn. He said to me ‘Frank, here’s a masterpiece. There’s nothing else exactly like it in the world. I know you can appreciate it. Here, I’m giving it to you!’

“And here’s a Cellini A diminutive bronze tilted in his large hands. As he talked, balancing it in his hand, his thumb stroked the back muscles. “There’s vitality.” Slowly the little man turned before our gaze, revealing the chaste fig leaf, compactly put, the buttocks. dimpled at the sides from drawn-up intenseness.

“And there,” he continued. “is the finest Oriental bit I’ve ever seen. Whistler said to me. as he looked at that fan. ‘Frank, that’s perfect - frame and all. And I don’t doubt you got it just as it was.’ I did. It’s perfect. Frame and all in Japan. What better could be imagined? Black, gold, and gray, with the peacock there to the center so… the little Japanese poem at the side. Whistler knew. They said I learned from the Chinese,’ Whistler told me. ‘but I didn’t. I like that sort of thing: and I’ve seen quite a little of it. But I was never influenced by it.’

“But here’s something you really ought to see. Augustus Caesar - of the time.”

“Of the time, hmmmm!”

“Bought it in a little town in northern Italy for 100 lire. The Museum of Naples offered m: a thousand.

“But come in here. Lots of things. Whole attic full. You’ll have to come up and see it. Sometime. You could write it up, maybe, for your paper. There’s a story … almost as good as the book…

“Lovely virgin.” he shot over his shoulder, throwing an explanatory hand at a lifesized wooden madonna with child standing mute and smiling as she had stood for five hundred years before she came to grace the atelier of the author now at 70-odd.

“And there is a Rodin by Rodin. lie gave it to me. And there’s a Renoir by Renoir. He gave it to me just before he died. And Cecil Rhodes. A Great Man! I guess that’s the best Cecil Rhodes in existence. And there’s the little statue of him that Tweed did. And there’s Uncle Woodrow! Uncle Woodrow - in the life- as he wanted them to see him! Thumbs in the armpits of his vest: the very caricature of mankind. My God! I got that in 1916 in Washington. On sale all over at the time. Look at it. Isn’t it monstrous? I got it for that reason. A man that occupied a time like no other in history. The greatest chance in history for a man.

“I remember when Otto Kahn came back from Europe he felt pretty strongly that we ought to get into the mess. ‘Frank,’ he said to me. ‘you know this is getting pretty bad. They’re going to wipe out France. Good God, man. we ought to do something, not sit back here like this! What can we do?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘personally I think the Germans ought at least to get a square deal.’ (They’d whipped the whole World. I thought they ought to get a draw, anyway.) I said, ‘But if that’s the way you fee! about it there’s, only one thing to do and that s to go right down to Washington and tell Wilson what you think.’

“Well. he went to Washington and talked to Woodrow. After he’d been talking awhile, he said: ‘Since you haven’t made any response or asked any questions. I assume you agree with me Mr. Wilson, in what I’ve said. You agree, perhaps, about this - and that -. You see what-‘

“ ‘Mr. Kahn,’ said Mr. Wilson,” - my host placed his hands preacher-wise and affected a drawling high-pitched tone of voice - the last three years I have forced myself to think of other matters. I have avoided contact with other intellects. I find that contact with any other intellect devitalizes me.’

“ ‘My God,’ said Kahn, ‘that was just what I’d been waiting for him to say. “Contact with any other intellect devitalized him! My God! The - - -! I could have put a bullet through his stomach!’

“Well,” my host sighed. returning to the grotesque long-legged statuette, the type of comic miniatures seen in the toy shops, “there he is as he wished others to see him.”

He revolved Mr. Wilson in his fingers and then set him back upon the mantlepiece, a sharp smile dominating us, a sharp nose jutting out above us, the figurine’s thumbs to his waistcoat armpits, feet widespread, surveying the notables of numerous nations…

“And there’s Tolstoi,” my host pointed to a pencil drawing of the old man, wide-winged in the nose, beady-eyed, strange. “Done by his son and given to me. And there’s Verlaine. And Wagner. And dear old Heine.

“And here’s a letter, in this frame, signed by the Duke of Wellington. In a smaller frame I had one of Napoleon’s but it got lost in moving. The carter said to me, ‘Was there really a letter there?’ ‘Yes,’ said I, ‘there was really a letter there - from Napoleon the Great! ‘I’m awfully sorry,’ he said, ‘but I didn’t take it. I didn’t see it!’ Ha, ha. From Napoleon the Great! Well it’s gone. When I was a boy something serious happened to me and I said to myself then. ‘Frank! If that had happened to anybody else you’d have laughed at it!’ Sometimes the laugh doesn’t go very deep - but come in here. You asked about my Book. I’ll show you.

“I was not joking when I told you the price. Lots of people - I get letters every day - write in and enclose their fifteen dollars and beg for copies. It’s a good book. The second volume, I have no hesitation in saying it, is the greatest presentation of a life ever written.”

We entered the bedroom, the brass bed still in process of composition under the hands of a fluffy-haired little French maid. A pink silk comforter and a spread of cream lace were rumpled at the foot. The room’s walls glowed with the pink flesh of nude women. On the wall at the head of the bed, at the right, were women of the last century in gilt frames or without the gilt frames, half-draped, in toilette preparation. Flung around the rest of the room, at all elevations, the ladies, were, like Art, ageless, and naked, styleless, or always in style. Looking down upon the bed from the wall was one, severed at the knees, but otherwise totally apparent, and elsewhere were ladies, full face, rear-face, side-face, seated, kneeling, recumbent, prone and supine, and on the eastern wall one, among many, so seated as to appear so explicitly female as to suggest nothing else.

As my host bent over to extract a copy or his book from a broken packing case, one’s associative faculties brooded.

“Of course,” one said, “you’ve read that book of Joyce’s …” My host straightened up suddenly, with his book in his hand.

“That poor book! Not a single good seduction in it! Six page, that were worth writing. Outside of that - nothing. If my book isn’t better than that. I’ll let them burn it. They do burn it in England. In the United States they confiscate them, and then sell them against me. Bookleg them, you know.”

I spoke of what the critics said of Ulysses - the concluding soliloquy of Mrs. Bloom.

“Oh. yes, the prostitute in the end,” he agreed. “No, that isn’t what I meant. -that’s no good. A Prostitute’s Musings. No. What I meant was six pages describing a girl … yearning to show everything she has, to the man she loves. Beautifully done. But also impossible. You know, there isn’t a woman in the world that would do a thing like that.

“Why look,” he seized my arm. “Once I went into Central Africa. I took a thousand pictures. No trouble at all. Girls would drop,” he put his hand on his groin, “their tablier,” he paused on the word, “without any hesitation at all. And let you photograph them any way you pleased. Absolutely dumb. Stupid. Savage. Why, those people couldn’t recognize their own pictures, nor the photographs of their brothers or sisters or fathers or mothers. Tried a week. Finally I took a picture of one old man with a crazy white beard, deformed, distinctive altogether. I showed them that and they recognized him - the only one. ‘Oh, ah, why. that’s so and so,’ they said. Well, now even those people had modesty. They’d let you photograph them naked, but the women covered themselves with a little patch and you ask them to take that off, and they’d hum and haw and twist around and refuse.

“And here Joyce has a 16-year-old girl … Well you know. I said to him, ‘Joyce, do you mean to tell me that a Dublin girl, 16 years old and in love with a man and raised to boot in the Holy Mother Church would want to do a thing like that?’

“ ‘Yes,’ he said. Well,’ I said, ‘you’re crazy. There’s Emma Goldman. She’s lived a lot. She’s a wise woman. We’ll ask her!’ We did. ‘Frank’s right,’ she said. And it’s true. Think it would scare the man away if he loved her. Think he’d think her ugly. I know. ‘Well,’ said Joyce. ‘she’d been with another man. She wasn’t a virgin.’ ‘Makes no difference.’ Well,’ Joyce concluded, ‘I know a girl who did do it. So there you are.’ I don’t believe it…

“But that’s all that is interesting in the book. The Portrait of the Artist is a better book. More to it. But Joyce has done good things. That Dubliners … But now if my book here isn’t better than Ulysses you can have it. I speak from seniority, of course; I’m considerably older than Joyce.

“But - I’m not modest. I told Wilde once that modesty was the fig leaf of ugliness. Only people who are ugly are modest. They have something to hide.

“Anyway, there it is,” he said. opening the volume of his confessions and displaying the illustrations rose, a la Vie Parisienne. “Had them done in Germany.” The pages whirred under his fingers. Here and there he stopped heir flight, pausing over a lady, recumbent. pink-toned, naked, with her hair around her shoulders, her hody warm-toned in the print.

“Rather nice, eh? Too much for the English though. McBride said to me, ‘Frank, put in those illustrations and I will sell 2,000 copies in Chicago in two weeks.’ Well, I put in the illustrations. But I didn’t in the second volume. The second volume is a big piece of work, Nothing like it. Oh, a few rough drawings, of course. But sketches, very conventional, at the ends of chapters, and so on, know.

“Am I doing anything for Mencken? No, not right now. You wrote for the Smart Set? Is that so? So did I. Maybe you’ve seen my things there. Of course! … Well … I made lots of money with Pearson’s. Maybe I’ll do it again. Lots of money. Until Burleson drove me out. Held up the magazine in the mails all the time you know. It was all right - five days, ten days. I was too wise for him. Hold it up and I’d advance the date of publication and keep on advancing it. But once he held it up for thirty-seven days and that ended it. Thought there was something seditious in it. It kept me dashing down to Washington all the time. ‘Frank,’ he’d say … What? No, Mencken wants stuff on Americans. Wrote me, ‘Frank, we’ll take anything you’ve got or can give us, on Americans.’ Well … John Reed, now. Who cares about John Reed? He’s dead. And I don’t know anything good I could say about any Americans. All I could say would be raps. And don’t particularly care to rap ‘em.

“When I was editor of the Saturday Review, the greatest assembly of literary men in history, I had a policy, and I believed in sticking to it. There was Shaw and Wells and Rowe and oh, everybody else. I called a dinner and I said: ‘Gentlemen, it has come to my attention that people outside have started to call it the Saturday Reviler. Well, this sort of thing doesn’t get us any place. Hereafter the Saturday Review is going to try to find stars, and if it can’t find stars, it won’t merely hurl bricks. What good does it do? Insults, raps, knocks! Mainly lies. Nobody’ll remember them in fifty years. If we can’t do something constructive,’ I said, ‘we won’t do anything.’ Well, worked.

“I printed the first stuff of Beerbohm, Wells. Why, who ever hear of Shaw before then - Shaw the Socialist, the play critic? Wells hadn’t written a single book at that time. We had an Englishman on the staff, reviewing. Oxford man, well-read, so on. I gave him a book and he turned back a review of it, damning it. ‘Frank.’ he said, ‘this is terrible. It’s no good.’ ‘Let me see the book,’ I said. I took it and opened it. ‘Why man,’ I said ‘give me that review.’ And I took it and threw it away. ‘We can’t use that,’ I said ‘Why, his first paragraph shows the man can write. Look at it! Listen to it! . . Wells,’ I said, ‘there’s a book. Read it and see if you can’t do something about it, if it deserves it.’ A few days later Wells came back to the office. ‘Frank,’ he said, ‘you told me to write a column and a half on that book. I’ve written five pages.’

“Well,’ I said, ‘what? Praising it?’ ‘Yes, praising it.’ ‘Give it to me, I said. ‘I can use it.’ I did. That was the first review of Almayer’s Folly. Conrad told me later that the review made him. It did. He wrote a lot afterward, but Almayer’s Folly was one of his best. Well, that’s something. now. l didn’t think quite as much of the book as Wells did, but the man could write.

“You know, just before you came. there was another American here. Brought me four or five stories. And a marvelous thing! Absolutely unheard of. One was a masterpiece! One of the most unusual stories I’ve ever seen. The rest, third-rate stuff.

“Here! You’re a newspaperman. I’ll give you a copy of my book. Wait a minute. I’ll inscribe it, if this crazy French pen of mine will work. Look at it. Isn’t it beautiful? Ornate as possible and useless as thev make ‘em. Like everything else French, almost. Yes, French pastry, lingerie. etc., you’re right. Except French girls. Don’t you dare to say anything against French girls. They know how to work, all right.

“There. And there’s the couplet that inspired the work. ‘Death closes all; yet something ere the end, Some work of noble worth may yet be done.’

“Ah, a marvelous sentiment.” He left me and walked up and down the room, his hands behind his back. “ ‘Death closes all …’ Well, it’s too late for a siesta, and my second secretary is coming in a few minutes, anyway. It’s all right … I’m going to have the reading of my play in a few nights. I’ll invite you over. I saw Shaw’s Joan - three fools sitting around a table for three hours talking about nothing. Talky, talky, the very worst kind. No life, no feeling. no fire. God! I’ve done another Joan of Arc. If it hasn’t got more to it than Shaw’s I’ll quit!”

I emerged into the quiet dusk of the Nicois winter afternoon. I was carrying down the hill the Book. All nature lay back in silence.

Comments